Products built with pride: a conversation with UXer Elena Agulla Gil

Insights, thoughts, and considerations from one voice in the LGBTQ+ community on how to more mindfully consider marginalised users.

Photo by Christophe Suant

“I can only speak from my personal experience as a non-binary person,” says Beyond designer Elena Agulla Gil, conscious of the weight of the conversation. “When we are talking about creating products for everyone, everyone needs to be part of the conversation of how to create them.”

Elena is both relatively new to Beyond and to the world of UX design, but has emerged as an important voice in that conversation — one that is thoughtfully considering and researching what it means to design inclusively with marginalized groups in mind, the LGBTQ+ community among them. The stakes are high: Users’ mental health and feelings of self-worth can be directly affected by design decisions made long before a product ships. Quoting inclusion experts and authors Corey Jamison and Frederick Miller, Elena says: “‘If we don’t intentionally include, we unintentionally exclude.’”

Informed both by research and lived experience, Elena shares a few thoughts on inclusive design and what it takes to build a product with pride.

Small decisions, big differences

“Sometimes what can be considered a small design decision can empower someone in a huge, huge way,” Elena says. Products often don't need to have big inclusive features as much as they need to provide an array of small options that allow users to personalize their experience.

“When considering trans and non-binary people, for example” Elena says, “this might involve providing more than two options for gender, a space for people to input their pronouns, or an alternative option to the traditional Ms. / Mrs. / Mr. if that’s information you need.”

Sometimes, though, the real decision is about whether or not that information is needed in the first place. The UK's inclusive design guidelines advise product designers and developers to only ask for biological information if they genuinely cannot provide their service without it. Otherwise, if the intention is just to, say, personalize an account page, consider offering personalization options that don’t rely on gender as a proxy.

“Sometimes what can be considered a small design decision can empower someone in a huge, huge way.”

Elena notes that even for the most basic information, it’s best not to assume. “When it’s necessary to ask for a person’s legal name, don't assume that is also the name they want to be greeted with when they log in unless you’ve also confirmed it’s their preferred name.” This design decision is a perfect example of the spirit of inclusive design — it accommodates not just those who have made a name or identity change, but also those who simply go by a nickname or don’t use their legal name in everyday life.

Invisible impact

“Ironically, inclusive design decisions are often invisible,” Elena says. A product doesn’t always have to shout, “I’m inclusive!” — it can often be quietly inclusive in a way that makes all people feel welcome.

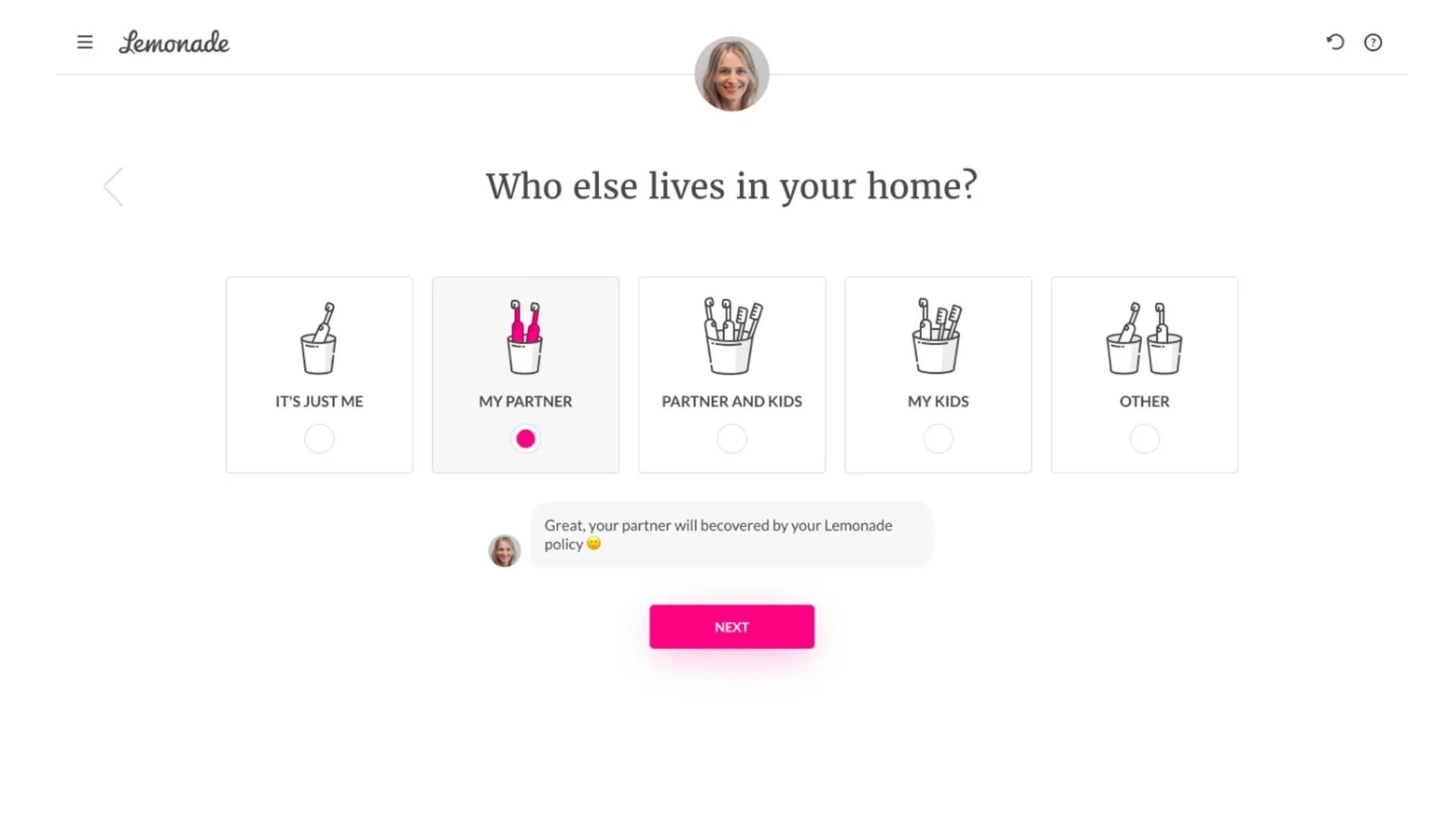

One example Elena points to is the onboarding experience with insurance company, Lemonade, which uses creative imagery involving toothbrushes to represent household size instead of gendered iconography:

“Sometimes you only realize when something makes you feel excluded, and you take it for granted when you feel a part of the fold,” Elena says. This is particularly true with digital products because by the time people have decided to use them, they already believe the products are right for them.

“In my experience, any type of design that doesn't align with a binary is a welcome experience. And sometimes that little bit can go a long way.”

Holistic thinking

Little bits here and there can add up, but only if the overall product experience is consistent with itself. Elena points to Instagram as an example:

“Instagram uses the word ‘their’ whenever you interact with another user’s profile, which is great.” This kind of gender-neutral language is exactly the kind of product design decision that allows LGBTQ+ users to feel naturally at home using the app.

However, Elena notes, this same inclusivity isn’t present across all parts of the product, particularly when it comes to Instagram’s algorithm. “At times, Meta has been accused of ‘shadowbanning’ queer and trans people on Instagram, which keeps them from reaching a wider audience and monetizing their content,” Elena explains. “Juxtapositions like these can make you wonder if a company truly believes in what they're doing or not.”

“There are obviously brands out there that are trying to do the best they can and are creating products that are inclusive from the get-go. But for a user to truly believe in it, everything about the product experience needs to be aligned and thought about holistically.”

Experience, expertise, and empathy

That kind of holistic thinking starts with involving people from the community for whom you’re designing—whether it be hiring them, consulting with them, or just spending time to understand their challenges.

“Sometimes we don’t realise a product is excluding a group of people until someone who’s a part of that group points it out to us,” Elena says. That becomes a lot harder if you don’t intentionally interact with anyone whose experience may be outside “the norm.”

“Sometimes we don’t realise a product is excluding a group of people until someone who’s a part of that group points it out to us.”

That being said: “You can't expect that just because a person belongs to a certain community that they will know everything about it — they will have a personal experience and that's it,” Elena notes. “So it's always important to consult with people whose specialty is in inclusive design and translating marginalized users’ needs into workable designs.”

This mix of lived experience and professional expertise is where the real work happens, but it’s all moot without empathy.

“There are people out there talking loudly about their experiences. If you genuinely want to learn, you’ll easily be able to do so. Just know that not everyone has the energy it takes to explain their experiences to other people because doing so often takes emotional labor. You’ll need to be ready to ask your questions to multiple people, to multiple groups and listen deeply to those who are willing to talk.”

Here again, Elena issues a reminder that they are a single voice in the conversation on inclusivity and reminds product designers to do their own research. “We all have a lens on things that’s shaped by our experiences and that varies from person to person. It's always good to get different points of view.” Even still, Elena’s point of view reminds us that what it takes to build a product with pride requires inclusivity, and that takes real work and genuine care for the people for whom you’re building.